A medium dog-sized carnivore that is able to take down on its own ungulates, survives the harshest winters far north and does not hibernate..

Well, there is an actual animal like that, the wolverine (Gulo gulo).

The wolverine is a great example of an opportunistic predator and scavenger. It will feast on anything it stubles on, taking huge advantage of any opportunity given.. While most of the time it’s looking for smaller prey and carrion, it can take down ungulates much larger than itself such as reindeer. It’s also a scavenger, with a very acute sense of smell, capable of detecting carcasses covered up by snow with great accuracy.

With frost and water resistant fur and paws of very large size, that help them to stay on top of deep snow, its anatomy is greatly adjusted to the conditions of arctic and boreal forests.

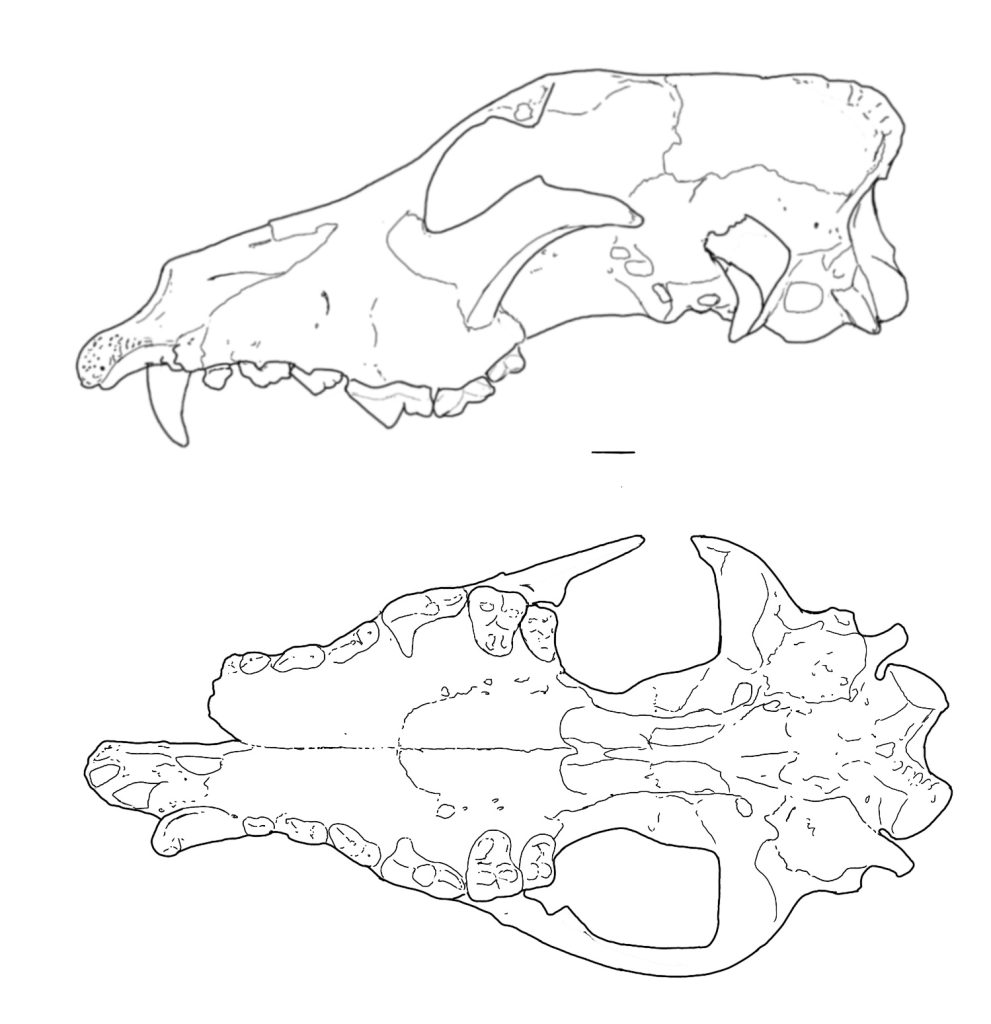

Its lifestyle and habits are reflected in the skull and dentition. When compared to their closest relatives, it posseses enormously enlarged carnassials (P4 and m1) to crush bones and also, the upper molars are rotated in 90° angle which enables them to tear off frozen solid meat. Overall, the skull looks like that of an absolutely formidable predator.

The wolverine is a member of Mustelidae, that means that it’s basically a giant marten or a weasel rather than a small bear. The members of the weasel family are known to have absolutely enormous capabilities relatively for their body size, which is only confirmed in this species.

To look a little bit at its background and history, among mustelids, the wolverine is most closely related to martens (Martes) and fisher (Pekania). Together forming the subfamily Guloninae. To whose of these is the wolverine more closely related isn’t 100% sure. It’s likely that their common ancestor looked similar to the fisher Pekania occulta.

I had the idea of reconstructing some of its ancestors, or closely related extinct species. What came to my interest, is this fragment of the lower jaw of the ancestor of wolverine, being classified in its own species Gulo schlosseri, from Żabia cave in Poland.

To highlight the proportions and life appearance of this animal with the best possible accuracy, I combined this material with skeleton of modern wolverine, which gave me a good base for my drawing.

With a decent “strolling” pose and proportions, the muscles were added very roughly. I chose it yawning, to show its stunning hypercarnivorous dentition mentioned above.

Since the animal, in life would be all covered in fur, no muscular anatomy would be visible. This has made the job a bit easier. Here’s the outline of it.

Then, the details…

And finally, coloration. Althought color variations in individual wolverines can be suprisingly variable, for this one, I chose more darkly-toned individual. Perhaps, all these populations were darkly colored because of their shared ancestry with the fishers (Pekania)? This is a matter of speculation :).

Here we have it. The reconstruction of Gulo schlosseri, an ancestral wolverine from Early Pleistocene. Acting more or less like its living descendants, it surely would have been an amazing experience encountering one of these in their natural habitat.

References:

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259810350_Early_Pleistocene_fauna_and_sediments_of_the_Zabia_Cave

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolverine

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324593778_A_new_species_of_Gulo_from_the_Early_Pliocene_Gray_Fossil_Site_Eastern_United_States_rethinking_the_evolution_of_wolverines

- https://wolverinefoundation.org

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Present-bones-grey-from-a-male-Gulo-gulo-individual-from-the-Sloup-Cave-Moravia-Czech_fig3_265923648